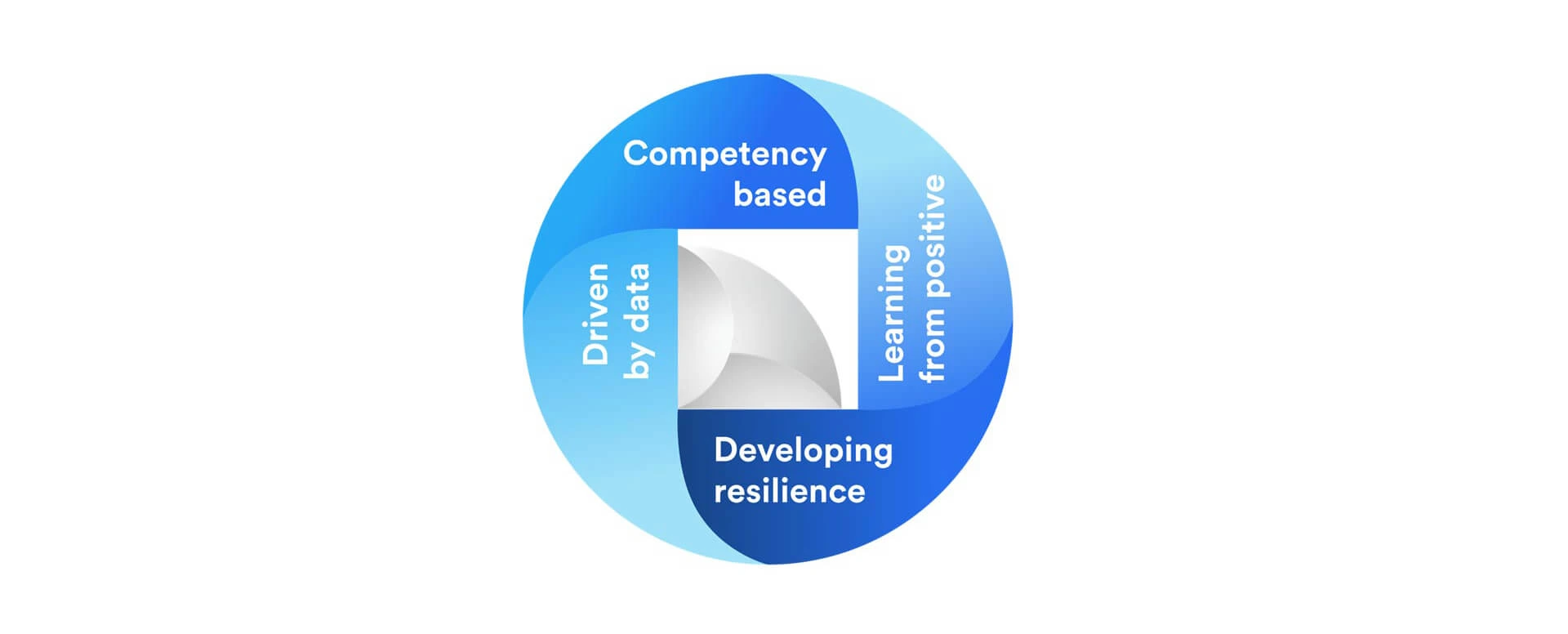

1 – Competency-based Training

Competency-based Training is a much-used term that can mean different things to different people. In the development of EBT we took a very deliberate approach which also underlies the concept of CBTA. One of the drivers for EBT was the need to maximize learning in a FSTD program, and this is only possible to achieve when we understand the objectives. Intuitively we believed that the focus of assessment on what were called “technical skills” did not support a learning process especially for more experienced pilots undertaking recurrent training. The system in service demanded perfection in a series of rehearsed maneuvers in a very narrow scope of operations. We took a more holistic view of the human in the technical environment and examined what is and what drives excellence in a modern cockpit. To support this, we had the benefit of many years of experience in the development of behavioral marker systems for CRM. Our idea was to create a vision of an effective pilot, including what had previously been known as “technical” and “non-technical” skills. This was done by taking advantage of pilot subject matter expert opinion worldwide. The process is very simple, asking experienced pilots about their role models; expert performers they admired and wanted to emulate. We continue to do this worldwide, and the results remain very consistent. The information given to us by pilots came from their observations and the consistency of what they said is remarkable. This in addition to a behavioral marker system created in the same manner by LMQ in the United Kingdom, published originally in CAA CAP 737 and validated in service, helped us to create strong Performance Indicators which naturally grouped into different areas of competency. This is where the 9 competencies originally developed came from. The power of this approach is that it comes from experienced practitioner pilots and not a committee of “experts” with an abstract view. The process was simply to ensure that pilot reflections were captured in a way that we could observe and measure in training. This work became the Competency Framework developed for EBT, and we believe it is important that pilots continue to determine its relevance to their world by providing feedback. The competencies came from pilots and are designed for pilots, written in language they can relate to in everyday operations. Competencies should drive everything from selection through ab-initio training to recurrent training. In EBT our focus is on processes in the cockpit. Effective processes drive strong countermeasures to Threats, Errors and Undesired States (TEM) and reliable and safe outcomes. The idea is simple, and it works.

2 – Learn from Positive

Our focus for generations has been identifying things that go wrong, and where appropriate practicing them until we can demonstrate a level of perfection in training. We can use here the example of the “V1 Cut” which has its roots in the 1950’s and 60’s when engine technology was much less reliable. This was a reaction to many engine-out events which led to catastrophic results. Of course pilots still practice for these events, but the scope of activity has widened substantially. There have been substantial developments in aircraft and engine design and reliability in addition to incremental improvements in aircraft maintenance and operations. We operate in a very safe system which means serious events are very rare. We also make the assumption that when flights are operated uneventfully, this is because all the systems and procedures are working as intended by the operator. The reality is often very different and in programs like LOSA we often observe crews working around ineffective processes and managing events not anticipated by design. When events do happen there is a tendency to focus on what went wrong and the factors which contributed to the event. There are many notable challenging events which have been effectively managed by the crew, but the tendency is to focus on what went wrong, often ignoring exemplary performance by the crew because they contributed only positively towards a safe outcome. If we are to strive for excellence this is exactly the performance we need to capture and make visible to crews. This principle also needs to be used in training, helping crews to identify performance and competencies which helped to drive safer outcomes. Whenever highly effective examples of crew performance are observed, it is vital that these positive behaviors be reinforced.

3 – Develop Resilience

Professor René Amalberti reviewed the following three answers to the question of why it is important to focus on a human factors strategy if safety programs are to be effective:

Reducing human performance variability by standardizing behaviors and thereby increasing overall system predictability is the main goal of aviation human factors strategies.

This must be accomplished in an aviation environment that is characterized by:

- High human variability. There is a large number of pilots with low behavioral predictability and a wide range of experience, cultures, and error propensity.

- High organizational variability due to differences among airlines in terms of such factors as size, maturity, operational styles, and subcontracting strategies.

- Low aircraft variability. As a result of advances in materials, components, and design, equipment failure is relatively rare and failure modes are highly predictable.

Resilience is a new challenge focused on anticipating problems, accepting a wide range of variability, adapting to unstable and surprising environments, and designing error-tolerant human/technical systems.

By simply repeating the same exposure in training year after year we become very good at anticipating and demonstrating performance to a level of perfection, albeit in a very narrow field previously demanded by regulation. The only way we can help pilots become more resilient to events is to significantly broaden their exposure in training. This exposure to threats which are unexpected and sometimes complex firstly will normalize the response to what we call surprise, when a human is under sudden stress, and will broaden the experience particularly of solving problems in the flight deck. At times we have become too regimented in our approach to managing threats. Things often don’t go as expected, and problems don’t occur the way we have imagined them or even trained for them. The more we can engage pilots in solving problems they have not anticipated, the more capable they will become in managing complex situations in operations.

4 – Driven by Data

Members of our team were involved in the original analysis for EBT initially published by IATA in 2013. The following is extracted and paraphrased from the Executive Summary:

At the inception of the EBT project, a review of available data sources, their scope, and relative reliability

was undertaken. The scoping, analyses and reporting were led by Capt. John Scully and his team with comprehensive analyses of the data sources chosen. The objective of these analyses was to determine the relevance of existing pilot training and to identify the most critical areas of training focus according to aircraft generation. The Data Report for EBT corroborates independent evidence from multiple sources, which include flight data analysis, reporting programs and a statistical treatment of factors reported from an extensive database of aircraft accident reports. Both process and results were peer-reviewed by experts in pilot training drawn from airline operators, pilot associations, civil aviation authorities and original equipment manufacturers, so as to provide transparency and to bring a qualitative and practical perspective. Pilots often do not have the confidence and capability to operate the aircraft in all regimes of flight and to be able to recognize and manage unexpected situations. Results show that manual aircraft control, management of go-arounds, procedural knowledge of automation and flight management systems (FMS), monitoring, cross checking, error detection and management of adverse weather are issues of concern. It is important that non-technical performance becomes part of an integrated approach to training, and the report reveals the significance of certain non-technical competencies in reducing risk in operations. The challenge of maintaining Situation Awareness in a highly automated and highly reliable system needs to be addressed through more effective training and exposure to rapidly developing and dynamic situations. Competencies of Leadership and Communication are revealed as key risk reducing countermeasures and should be a primary area of focus in training. Data indicate a need for pilots to be exposed to the unexpected in a learning environment, and be more challenged and immersed in dealing with complex situations, rather than repetitively being tested in the execution of maneuvers. Training programs constrained by repetitive testing in the execution of maneuvers to comply with outdated regulation, lack the variability to train effectively in this way. The report indicates significant differences across what can be considered as three different aircraft generations of jet transport aircraft and two generations of turbo-prop aircraft. While overlap in training clearly exists, there are quite distinct generational differences in patterns of existing risk that are not adequately addressed by current training.

What we have learned is that the EBT program, consisting of a structure of training topics derived from data delivered over a 3-year cycle provides flexibility for operators to tailor exposure in training to the risks identified by their management system.